- Home

- David Crookes

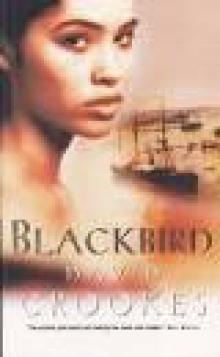

Blackbird

Blackbird Read online

For Val 'The stylish plot twists will satisfy the most avid reader.' Who Weekly (Page-turner of the Week)

'Crookes creates a fine fiction from appalling truths. That is Blackbird's success.' Gold Coast Bulletin

'Crookes unveils Australia's suspect past in a natural and engrossing style.' Melbourne Herald Sun

'Splendid Reading. In the realm of Joseph Conrad ' The Catholic Weekly

BLACKBIRD

by David Crookes First Published in 1996 by Big Indian Pty Ltd Republished in 1998 by Hodder Headline Australia Pty Ltd Republished in 2000 by Hodder Headline Australia Pty Ltd (Twice)

This ebook edition published in January 2011 by Big Indian Pty Ltd Copyright © David Crookes 1996

CHAPTER ONE

Something was wrong.

There was no sign of life on the island’s pristine long white beach and no sound from the jungle beyond. Except for the tiny wavelets gently lapping against the shore, everything was absolutely still. The whole island seemed too silent to be real.

A ship’s boat splashed noisily into the sea. From his position at the rail of the brigantine Faithful, Captain Isaiah Cockburn looked on apprehensively as the oarsmen of the small craft dipped their blades into the crystal clear turquoise water of the anchorage.

Moments later a second boat, followed quickly by a third and fourth, pulled away from the vessel. When the small flotilla passed over the island’s fringing reef, the leading boat made directly for a coconut grove on the long white beach.

At Bougainville, Cockburn’s task had been easier. As soon as the Faithful arrived at the island, scores of friendly natives paddled out in canoes loaded with yams, fruit and shells. His crew had shown them brightly colored cloth, rolls of calico and knives, and indicated their willingness to trade.

When the eager islanders clambered aboard, crewmen led them down to the ship’s hold where all kinds of goods and trinkets were displayed for trade. Then the hold hatches were slammed shut and hastily locked, and yet another hapless group of Melanesians were destined to cut cane in Australia on the sugar plantations of the British Crown Colony of Queensland.

The captain drew a bulky silver timepiece from a waistcoat pocket and held it as close to his eyes as its restraining chain would allow. It was two minutes to noon and oppressively hot in the lee of the island which sheltered the Faithful from the persistent southeast trade wind blowing over the Solomon Sea.

Cockburn stretched his tall frame and cursed the heat. Even in July, the middle of the southern winter, the sun was merciless in the offshore islands of New Guinea. He put the timepiece away and raised a well polished brass telescope to an ageing but clear blue eye. Ever so slowly he scanned the entire length of the beach. Still there was no sign of life.

The captain shook his head. He had been expecting more.

Just three months earlier in April 1883, the self-governing colony of Queensland had assumed Imperial powers and annexed the eastern half of New Guinea, including these outlying islands, for the purpose of ensuring a plentiful supply of black labor for the colony.

The smell of stale sweat and molasses assailed Cockburn’s nostrils. Without taking his eyes off the ship boats, he knew Ned Higgins, the Queensland Government agent assigned to the Faithful, had finally awoken and found his way up to the deck.

Higgins joined Cockburn at the rail. He cleared his throat noisily, then lazily spat what he had gathered over the side of the ship.

Cockburn tolerated the repugnant drunk aboard his otherwise tightly run ship only because of the certainty of Higgins turning a blind eye to breaches of the regulations supposedly governing the labor trade, providing his appetite for rum and women was suitably satisfied.

Higgins pulled a flask from his coat pocket. He took a long swallow, then wiped his mouth with a dirty hand.

‘You’ll be sure to take aboard a Mary for me, won’t you Isaiah?’ The agent’s face broke into a near toothless grin. ‘Some say the Kanakas of these islands are the best looking of all the islanders of the Solomon Sea. There are no blue-blacks here Captain, like the savages of Bougainville. These people, I am told, are the color of creamed coffee and some of the females are uncommonly handsome.’

Cockburn turned an unappreciative eye to the little agent beside him. Higgins had neither washed nor shaved in the four days which had passed since the Faithful left Bougainville with three quarters of her licensed quota of living cargo—seventy five terrified and now halfstarved islanders, packed like sardines below decks in the brigantine’s stinking coal-black holds.

‘Yes Ned,’ Cockburn growled. ‘We’ll get you a Mary if we can, but as you can see, it looks as if this island is deserted.’

‘May I Captain?’ Higgins held out a bony hand.

Cockburn handed him the telescope. Higgins screwed up his ferret-like face and peered through the glass.

The boats were almost at the shore now. Higgins focused the lens on the first boat just as it reached the island. He watched as two figures in flowing robes and wide-brimmed hats stepped over the gunwales onto the sand. He laughed out loud ‘Got Bates the recruiter and Geddes the interpreter in missionary frocks eh! Isaiah? he said. ‘It’s an old trick but it usually works well when the savages are afraid to show themselves.’

*

Kiri crouched low in the undergrowth just a few yards behind the palm trees lining the beach and watched the white men pull their boats up onto the sand. The villagers had first seen the brigantine at dawn when she appeared on the horizon to the south. They had ample time to plan for the arrival of the ship while she nosed her way slowly up the shore-line, carefully avoiding the profusion of coral heads close in to the island.

Eventually the ship had anchored off a rocky point close to a deep channel between their island and a smaller neighboring island. Since then Kiri had just watched and waited. She began to tremble. It hadn’t been long since a similar ship had visited her island. The young men who had paddled out to greet it had never returned, and their families had wept when their empty canoes were washed up on the beach.

A parrot screeched in the bush behind the palms. It was the signal from her father, the village head-man. Kiri rose to her feet and walked out onto the sand. She was a sight to behold. She was naked, which was the way of all her people, but her sheer beauty and loveliness had always set her apart from even the most attractive of the other island girls. Her features were exquisite, almost regal in their perfection, and her skin was a rich golden brown, smooth and unblemished.

As she walked, she raised her arms and ran her fingers through her hair, smiling provocatively at the wide-eyed, unkempt group of ruffians now assembled on the beach. She stopped about twenty yards from where they stood and their eyes feasted on her tantalizing supple brown body, the upward sweep of her firm young breasts, and the promise of delight in the darkness between her thighs.

Two of the men who Kiri took to be head-men, had their bodies completely covered with long flowing robes and wore wide-brimmed hats over their heads. Kiri had seen similarly dressed men come peacefully to the islands in the past. Some had even stayed for periods of time on the island and tried to teach the islanders the ways of their white God. But such men had never taken any islanders away in their giant canoes.

‘Bless you my child.’

The words were spoken by one of the men in robes in a tongue Kiri didn’t understand.He held out his arms and walked towards her.

The parrot screeched again and Kiri turned and ran down the beach. As she ran she looked behind her. The two men dressed as missionaries were in hot pursuit with their skirts raised up to their waists. Underneath their habits they wore sea-boots and had long barreled American revolvers stuck into wide seamen’s belts. The rest of the men were close behind, laughing and shouting,

clearly enjoying the chase.

Nearly a hundred yards down the beach Kiri was still well ahead of her pursuers who were making heavy going in the loose sand above the tide mark. She deliberately slowed, then turned and ran through the palm trees into a clearing where several upturned canoes lay in the sand. Then she stopped and waited.

It was a few moments before Tom Geddes, the Faithful’s interpreter, who in truth had a scant knowledge of only a handful of the hundreds of languages of Melanesia, came panting into the clearing. During the chase he had cast off his long grey habit in the interest of speed.

When he saw Kiri standing still and smiling again, his face broke into a wide grin. He knew he had won the race and he moved toward her, anxious to collect the prize.

The spear came from nowhere. It passed clear through Geddes’ sweaty neck just as the rest of the runners burst into the clearing. Geddes drew his pistol an instant before a second shaft pierced his heart, and the weapon discharged harmlessly into the air as he dropped stone-dead to the ground.

In the mayhem that followed, some thirty or forty howling islanders, all strongly built young men, leapt from the bushes throwing spears and swinging clubs. Many found their mark before the surprised intruders were able to defend themselves. But when the sailors drew their pistols, they fired rapidly and indiscriminately, killing and wounding islanders with almost every shot.

Kiri had hidden behind the canoes the moment the first spear had been thrown. She heard a sound behind her. She spun around and saw Bates the recruiter, also seeking shelter from the melee. He still wore his missionary’s habit and blood poured from a gash in his forehead. He lunged at Kiri and smashed his pistol across her face, then drew her body in front of his own as a human shield.

Two islanders bounded toward him. Bates shot them both at point blank range, then screamed at the top of his voice:

‘To the boats lads, before they kill and eat us all.’

*

‘Make sail.’

The crew of the Faithful jumped to it when Clancy the mate roared the command. Mainmast halyards raced through clattering blocks as canvas fell from the forward yards.

Isaiah Cockburn’s eyes squinted into the sun as he peered aloft to assess the strength of the wind. The Union Jack fluttered lazily from the forward masthead. On the mizzen-mast, a catspaw caught the flag of the Faithful’s owner, the Stonehouse Shipping Company. The small gust caused the pennant to stream out momentarily displaying the company’s emblem: a medieval greystone tower emblazoned with the letter S, in red ,set against a solid black background.

Cockburn cursed the light air and moved to the rail. He raised his telescope. Just two boats were returning to the brigantine. Both were fighting a running battle with war-canoes which had put out from the shore after them.

He counted four men and a Mary in one boat, and five men in the other, seven short of the sixteen who had gone ashore. Cockburn waited until the boats had passed over the reef, then signaled to the mate.

Clancy’s voice roared again: ‘Weigh anchor.’

Crewmen bounded to the capstan. It spun around freely at first, then creaked and groaned in protest when the slack came out of the hawser. Strong backs bent to the task and the anchor broke free just as the boats bumped against the ship’s hull.

As the Faithful began to make way, the survivors of the landing party scrambled from the boats under a hail of spears and frantically climbed up rope webbing draped over the side of the ship. Up on deck, Cockburn, Clancy and Higgins leaned over the rail and fired revolvers at the war-canoes in the water below.

Halfway up the rope webbing Kiri tried to jump into the sea. Bates angrily slammed her head hard into the side of the ship, then dragged her unconscious body by the hair up behind him onto the deck.

Crewmen hastily sheeted home the brigantine’s sails and gradually the Faithful left the island of Kiriwina behind her.

CHAPTER TWO

It was raining in the diggings. For over a week Ah Sing had suffered alone. He lay huddled between filthy blankets in his tiny humpy dug into a hill-side above the Palmer River. In daylight the hut provided a clear view of the Palmer. But it was night now, and Ah Sing knew his old eyes would never see the river of gold again.

The old Chinaman had panned the Palmer for over eight years. He had been one of thousands of his countrymen to arrive at the far northern Queensland port of Cooktown from southern China in 1875 to join the great goldrush.

Ah Sing coughed and brought up blood. His frail body shook incessantly from the fever which for weeks had just refused to go away. He lay on a dirt floor which during the rain had slowly turned to a spongy mud. The dampness only added to his misery. First it had seeped though the blankets and then into his clothing.

Ah Sing's body convulsed in yet another coughing spasm, and when it eventually subsided he closed his eyes and prayed that when death came he would not be alone. *

Ben Luk was born in the colony of New South Wales. He too had worked the Palmer diggings for years. He had come with his father from the well worked southern goldfields,

lured northward by tales of the incredible wealth of the Palmer—a place where Chinese greatly outnumbered white men. Ben's father never saw the Palmer goldfield. He was one of hundreds of diggers murdered by marauding Aborigines on the long and dangerous road from Cooktown to the Palmer River. Somehow Ben had escaped, and it had been Ah Sing who had taken in the fifteen year old son of a Celestial father and a long since dead European woman, when all others of both races rejected him.

Now Ben was a grown man and the Palmer was all but played out. He had scoured the length and breadth of the goldfield over the past two years and found barely enough gold to provide food and supplies.

Most of the white men had gone years earlier, leaving behind them a fortune in gold to the Chinese who had the patience and determination to methodically work every inch of the entire goldfield and river bed. But now even Chinese on the Palmer were few and far between. Ben knew it was time to move on.

At twenty three, Ben Luk stood six feet tall and was powerfully built with a strong honest face. He wore his long black hair in a pigtail like a Chinese, but wore European clothes. He rode a fine chestnut mare and carried a carbine and stock-whip for protection, not only against Aborigines, but also against those Chinese and Europeans alike, who made no secret of their hatred for his mixed blood. Over the years in the wild Palmer country Ben had become proficient in the use of both the rifle and the whip.

Ben urged his horse through a swollen creek, just upstream of the point where it gushed into the Palmer River, then continued along the riverbank in the darkness towards Ah Sing's shack. Soon he would tell Ah Sing of his plans to move on and encourage the old man to leave with him.

Ah Sing's humpy appeared through the deluge. There was no light shining. Ben quickened his pace. When he pushed the door open and called out Ah Sing's name, there was no answer. He rummaged around and found an old miner's lantern and lit it. When the glow fell on Ah Sing's face Ben thought he was dead.

Ah Sing lay perfectly still, his eyes closed and his mouth hanging wide open. But when Benlifted him from the pile of wet blankets and laid him in a dry place, the old man's eyelids fluttered and he tried to speak.

Ben fetched a flask from a saddlebag and put it to Ah Sing's lips. At first Ah Sing gasped when the brandy seared his throat, but soon he felt it's warmth and spoke.

`Stay close to me Ben Luk. I have little time to say what I must say before I pass on...'

`I will not leave your side again,' Ben said softly and took Ah Sing's frail hand in his.

`I have told you before Ben Luk,' Ah Sing wheezed, `I was once a successful merchant in Hong Kong, but foolish gambling led to the loss of all I possessed and my creditors sent me in servitude to this awful wilderness to repay their due in gold.'

`Yes, yes.' Ben said softly, `but surely the many shipments of gold you sent to Hong Kong must have more than repaid your indebtedness.'

&

nbsp; Ah Sing began to cough again. His little body shook violently as he retched and gasped for air. His bony fingers clutched at Ben and drew him closer. `Some time ago I happened upon many large gold nuggets...more than enough for me to return to China with dignity...'

Ben felt Ah Sing's grip weaken. He watched as the old man's eyes closed again and he began to slip away.

`The large nuggets I found are buried deep in the ground directly beneath where I lie.' Ah Sing's thin lips barely moved when he spoke.

Ben knew the end was near.

`Take them,' Ah Sing murmured softly. `They are my dying gift to you. Leave this miserable place. Go to the capital of this colony, and take your place in it as a merchant, as I did in the colony of Hong Kong. Your mixed blood gives you the patience and frugality of the Chinese, and the forcefulness and tenacity of the English. Use these things to your advantage Ben Luk. Remember all I have taught you. Do not allow yourself to become indebted to anyone, and you will surely succeed.'

Ben felt Ah Sing's body relax. The old man's wrinkled face looked at peace now. Ben took Ah Sing into his arms and comforted him long into the night.

The rain had cleared by morning. Ben laid Ah Sing to rest in a deep grave beside a large flat rock on the hill overlooking the river. Immediately afterward he started digging up the floor of the humpy.

It was late in the day when Ben uncovered two Chinese earthenware jars. They lay side by side nearly three feet below the surface. Each jar contained gold nuggets, all much larger than any he had ever seen before. Ben estimated there were at least a thousand ounces of gold in each jar. For a long time he just sat and stared in wonderment. Later he returned one of the jars to the ground and carefully re-buried it.

The next morning Ben stood beside Ah Sing's grave, and with his head bowed he paid his last respects:

`I leave you now Ah Sing, where your spirit may watch the river from this great rock as I have so often seen you watch in the past. I shall not waste what you have given me.Should I fail as a merchant because of my ignorance of business matters, or should I somehow lose the wealth with which you have entrusted me, then I shall return for the second jar of gold which I have left with you for safe keeping. In this way, if necessary, I shall have a second chance to fulfill your wish that I use your gold to become a successful merchant.'

The Light Horseman's Daughter

The Light Horseman's Daughter Blackbird

Blackbird